We are running the SCIP summer program for current and incoming SFSU students in Bio / Chem / Public Health. Go here to sign up.

Email Marisol Flores and Judy Abuel at Sfsu.scip@gmail.com with questions.

We are running the SCIP summer program for current and incoming SFSU students in Bio / Chem / Public Health. Go here to sign up.

Email Marisol Flores and Judy Abuel at Sfsu.scip@gmail.com with questions.

The other day I was reading science writer Ed Young’s essay about birding in the New York Times. He writes about how he enjoys watching and recognizing birds. How it makes him feel closer to nature and how it made “things fall in place.”

His essay made me think of a feeling I have when I am back home in the dune landscape near where I grew up in The Netherlands. About once a year I have the opportunity to walk through that landscape and in addition to the pleasure of hanging out with my family, I enjoy recognizing and knowing the names of the plants we see. I definitely don’t know all of the plants, but I know many more in The Netherlands than in my chosen home of San Francisco. And recognizing these plants feels good. A little bit like seeing old friends.

A favorite of mine: slangenkruid – named after the pink, snake-tongue shaped pistil.

I didn’t learn about these plants as a kid. As far as I remember nobody in my family was interested in plants – and I certainly wasn’t! But later, as a biology student, I took botany and plant ecology classes that included many field trips where I learned about plants. In some cases, I still remember who taught me the name of a specific plant. These plants and their names make me feel at home and connected with nature.

When I feel that connection with nature, I resolve to learn more Californian plants too, so that I will feel more at home there. But it’s hard and I am not a student anymore who takes weeks long botany classes and who does ecology field trips. And there are so many plants here in California, I am not sure where to start. I did recently make some progress with the local birds though. While nothing compared to Ed Young’s progress, I have learned to recognize the most common birds in the park where I walk my dog. And now, when I see the black and brown of the dark-eyed junco or the beautiful red of the house finch, it feels a little bit like seeing friends – even if I only met them a couple of months ago.

Recognition brings joy. Whether it’s recognizing plants, birds or people. I believe that that is the reason why people like to read about the royal family and Jennifer Anniston.

And on the other hand, not knowing, not recognizing doesn’t feel good. Being lost is frustrating. And I am lost often. I work on antibiotic resistance, but can’t seem to remember the names of the relevant drugs or genes. My kids talk to me all the time about Pokemon and Zelda, and I just can’t remember any of the names of the relevant characters or places.

There is a similar issue with music. I love music, but find it hard to listen to artists and songs I don’t know yet. My taste evolves very slowly. So this year, with Beyoncé and Taylor Swift making headlines with their record-breaking tours, I wanted to get to know these two stars and their music (I know, I am like, two decades behind). My students kept talking about Beyoncé, but I didn’t really “get” her. She has a hundred hits and (don’t hate me for this) these songs all sort of sound the same to me – until last month that is. Beyoncé’s new country album brings me joy because it includes plenty of things I know and recognize.

This new album (Cowboy Carter) includes songs I know (Jolene and Blackbird) and voices I know (Miley Cyrus and Dolly Parton) – and with that, it made the entire album accessible to me. This, in turn, made me appreciate Beyoncé’s voice and made me curious about her other albums. I very much like knowing that Beyoncé, just like me, enjoys listening to Dolly Parton – we have something in common. Also, Beyoncé’s version of Jolene is great!

It may sound strange, but both recognizing the house finch and knowing a Beyoncé song, they both make me feel at home in this country and in this decade. And while it is often fun to be a foreigner, it is lovely to feel at home.

Last summer gave a talk at a Gordon Conference about transmission and evolution of drug resistance in HIV and E. coli. When I was done with my talk, there was time for questions. Dmitri Petrov asked what I thought about why resistant and susceptible strains of bacteria co-exist. I had to admit that I hadn’t really thought about that.

This question of co-existence (why aren’t all bacteria resistant or all of them susceptible?) it not a new one. In fact, about a week after the Gordon Conference, I talked to Marc Lipsitch who has worked on this question for many years. It was just not on my radar. Until last summer.

The question of co-existence marinated in my head for over the summer. I read papers about it. Looked at the data I was analyzing. And then sometime in the fall it suddenly hit me! I saw a solution to the question that was real easy. This is what I think may be happening: Resistance evolves when a bacterial strain finds itself in a person who is treated with antibiotics. But because most of us aren’t on antibiotic treatment most of the time, these resistant strains tend to have lower R0 values than susceptible strains (that is, the resistant strains don’t spread as effectively). Therefore in the human population at large, existing resistant strains are losing against the susceptible strains.

I had been studying the many origins of resistance (resistance in E. coli and other bacteria evolves very often – lots of convergent evolution), and I had been studying the cost of resistance (I think most resistant E. coli strains tend to die out – thought this is not easy to prove). These two ingredients together can explain the co-existence of resistant and susceptible strains.

Early October I emailed Dmitri: “Dmitri, I think I have the answer to your question!”. Dmitri answered: “Exciting! But you forgot to attach the manuscript”. Me: “Oh, I didn’t write it up yet! It is just in my head.”

So I started writing because that’s how academic science works!

The manuscript now lives on Medrxiv. I have submitted it to Nature (desk-rejected) and to Science (reviewed and rejected). Traditionally, after a rejection from a high-profile journal, one would send a manuscript to another journal right away, but one of the reviewers from Science suggested using a particular Norwegian dataset, instead of the Enterobase data I had used for the manuscript. I really liked that idea (as well as some other ideas from the reviewers). So I decided to pause and do more analysis. Some of the new data made their way into my talk for the TAGC conference in Washington DC last week.

If you are curious to hear where I am at with this project, here is the video of my talk:

I am a big fan of Dr Paul Turner from Yale University. He is good at many, many things. He is a very successful scientist (member of the National Academy of Sciences), has held several different administrative positions, created a company and does important science outreach work, including lectures available on YouTube.

I first met Dr Turner at the GRC microbial population biology conference he chaired in 2013. This was my first GRC meeting and I was impressed and inspired. The science was super exciting and the meeting was more diverse than any meeting I had ever been too.

His work as an evolutionary biologist who studies microbes is just amazing. I first got to know him for his basic evolutionary work on adaptation in viruses. Later, I learned about his work using evolutionary principles to prepare phage cocktails to treat people who suffer from drug resistant bacterial infections. For me, that phage work is one of the coolest applications of evolutionary principles ever. Here is Dr Turner doing a TED talk about that work:

The interview below is meant for a book chapter for a book about evolution for German high schools, but Dr Turner allowed me to print it here as well.

Dr Paul Turner: I am both a professional scientist as well as an educator, in my job as Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, USA. Most of my time is spent running a large and active research group, composed of postdoctoral, graduate student and undergraduate scientists doing projects on virus ecology, evolution and genetics. I educate them through mentoring and training, either working with them on projects one on one or in collaborative groups, often involving other scientists at Yale and elsewhere. My job as an educator also involves classroom instruction in undergraduate courses, and leading seminars taken by graduate students.

Dr Paul Turner: My fascination with evolutionary biology occurred around the time that I attended middle school and high school, nearby Syracuse, NY. I’ve always been an avid reader of science fiction, but my go-to nonfiction books at that time usually concerned the evolution of biodiversity, especially collected essays by Stephen J. Gould, the deceased Harvard paleontologist who was a prolific essayist for Natural History magazine. I greatly enjoyed reading Gould’s essays on evolution, geared to a lay audience.

It was during graduate school that I became obsessed with microbial biodiversity, and the awesome power of microbes as models for rigorously studying evolution questions, and the need to understand the ecology and evolution of microbes, the most abundant and biodiverse inhabitants of Earth. Unlike most microbiologists, my lab conducts research on a broad diversity of microbes, including a wide variety of viruses and bacteria that do and do not cause diseases in humans. Essentially, my childhood fascination with biodiversity prompted me to establish an ever-expanding microbial zoo in my laboratory, harnessed for studying an equally diverse set of basic and applied questions relevant for microbial evolution.

Dr Paul Turner: Ever since phages were discovered around the early 1900’s, scientists started examining the successful abilities for phages to kill bacteria infections in animals and people. One important researcher in these early efforts to do phage therapy was the co-discoverer of phages, Felix d’Herelle. There are many benefits of this approach, especially the ability for lytic phages to kill specific bacterial cells while releasing hundreds of new virus particles that can repeat the process in other susceptible cells; this is a rare example of a self-amplifying drug. Also, phage therapy seems to be generally safe for humans and causes few if any side effects, as long as the phage preparation is carefully produced to remove any dangerous bits and pieces of the bacterial cells that were destroyed while preparing phage doses; otherwise, these cell remnants are endotoxins that can cause a bad physiological response in the patient. However, phage therapy became unpopular in Western countries only a few decades after d’Herelle’s work, as these scientists and physicians instead invested in the development antibiotics to treat bacteria diseases, following Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin. Now that antibiotics are failing worldwide in their usefulness to treat antibiotic resistant bacteria, there is resurged interest in phage therapy as a possible alternative. Today we have much better microbiology tools and understanding of phage biology compared to the early 1900’s, when there was suspicion that the biological variability of phage doses was less trustworthy than purely chemical preparations of antibiotics. This gives us better confidence that these viruses can help treat infections, since antibiotics are waning in efficacy.

Dr Paul Turner: I have always enjoyed the challenge of experimental design, which is a very fun and creative process. There are endless mysteries in the natural world, but it is not trivial to design a biological experiment properly to test a hypothesis. I greatly enjoy interacting with members of my lab group and with other scientists, as we grapple with different ways to test our ideas using data generated in the laboratory, and by analyzing biological samples from natural environments or the human body. The ease and efficiency of growing many microbes in this process allows us to generate results quickly, and to rapidly address different hypotheses in a relatively short amount of time.What part of your job do you find difficult?

Dr Paul Turner: I greatly enjoy teaching in the classroom, but I am often amazed how much time and preparation is needed to create a well-organized and useful lecture. This is a difficult process, even though it is incredibly rewarding when I am successful in transferring knowledge to my students. It can be even more challenging to present complex scientific data and ideas to a lay audience of non-scientists, but I find this difficult task to be essential; I believe modern day scientists should embrace our role in trying to explain why science is important and how it impacts everyone’s daily lives.

Dr Paul Turner: I am incredibly grateful that I had an opportunity to live and work outside of the USA during my professional training, as this gave me a glimpse into how scientists in other cultures may approach similar problems in different ways. Unraveling the complexities of the natural world benefits from applying different viewpoints and life experiences, which alone reminds us why it is important for science to embrace diversity of the individuals studying it.

Dr Paul Turner: I love science, but I am passionate about many other things as well. I have a spouse and two daughters, and we enjoy getting outside for hikes and other recreational activities in natural lands, such as forests and the beach. Also, I have always enjoyed listening to music, and have a large collection of vinyl records that has grown ever since my childhood. I also like to read books for pleasure (not just for work), and especially enjoy science fiction novels and look forward to seeing movies made from them.

Dr Paul Turner: Yes, I find writing to be very enjoyable and perhaps the only downside is that scientific writing can be rather formulaic. Therefore, I also try to write review and opinion articles, where I can express my creativity a bit more. My goal is to write a science fiction novel some day!

Dr Paul Turner: I believe that drug resistance will always prove challenging for humans, as we grapple with emerging pathogens that threaten the health of humans, as well as that of domesticated plants and animals, and species that we are trying to preserve through conservation biology efforts. Thus, I admit that I am pessimistic that we will ever truly conquer the problem of drug resistance. However, I am increasingly optimistic that better science and engineering tools and expanded perspectives on the natural world will allow us to use creative approaches to solve difficult societal problems, including the challenges of drug resistant pathogens.

If you would like to learn more, have a look at Dr Turner’s website.

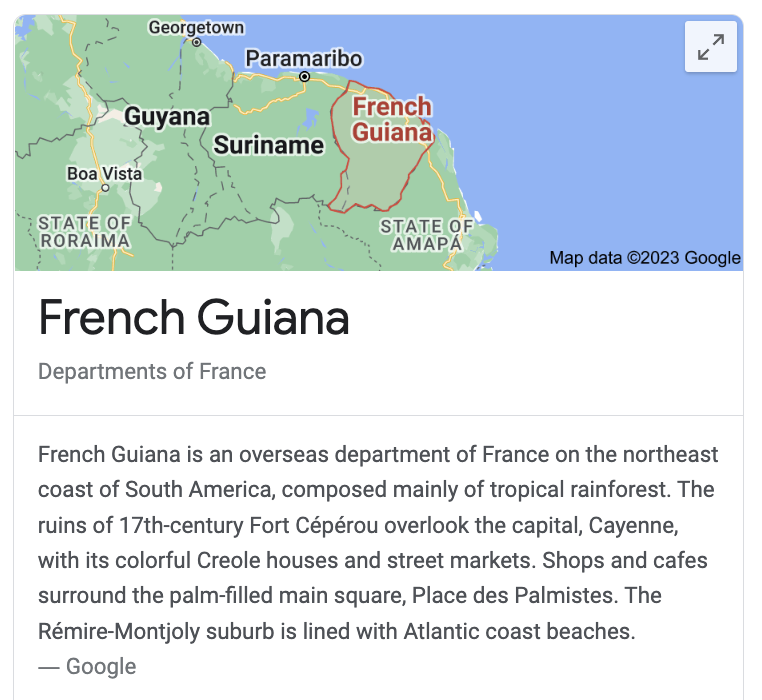

Dr Lise Musset is a malaria researcher in French Guiana in South America. I learned about her work years ago. In 2005, she published a paper to show that resistance to the drug Atovaquone is very rare in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Then, in 2007, she published another paper that showed that Plasmodium falciparum can evolve to become resistant to Atovaquone inside of people who are taking the drug to treat a malaria infection. There seemed to be an interesting contradiction here. Why is this type of resistance rare, even though we see that it can evolve within patients? Usually when resistant strains of malaria evolve within a patient, they will then spread from patient to patient, which makes the resistance become more common. The combined results of Dr Musset’s papers therefore suggested that the resistance is uncommon because, even though it can evolve, the resistant parasites cannot spread to other patients.

Much later other researchers showed that the resistant parasites cannot survive well in mosquitoes. This is a classic example of a tradeoff: a genetic change makes it so that the parasite can survive in the presence of the drug Atovaquone, but the same genetic change makes it unable to survive in a mosquito. Good for us and interesting science!

I wanted to ask Dr Musset about her work in French Guiana. In case you are wondering, French Guiana is in South America and it is part of France.

Pleuni: Can you tell me what your job is?

Dr Musset: I am a pharmacist and research director at the Institut Pasteur de la Guyane working on malaria. My work is passionate and very diverse, being a health professional as a medical biologist, researcher and expert in public health.

Pleuni: You studied to be a medical doctor, is that right? – but you work as a researcher. How did that come about?

Dr Lise Musset: I studied to become a pharmacist, which I am, but I rapidly wished to specialize in research. My main motivation during my education process was always to keep the maximum number of doors open. Therefore, in addition to the pharmacist diploma, I began to prepare for a Master in Science and then, to defend a PhD in parasitology. My curiosity and my origins from the tropical area probably played a role in the choice of research in infectious diseases mainly observed in the tropical places of the world.

Pleuni: What is the most fun part of your job?

Dr Lise Musset: My favorite part is when we analyze the results obtained after a long process which generally begins with writing a project, raising funds and all the administrative and ethical parts. Also, I really like to go in the field, in contact with people living in malaria endemic regions and try to implement operational research projects to enhance malaria care. My research is at the frontier between fundamental research and public health because my lab is a reference lab at the national (National Reference Center) and international level (WHO Collaborating Center). Our final aim is always to improve care.

Pleuni: What part of your job do you find difficult?

Dr Lise Musset: The most difficult part is to valorize the data and to publish them. Writing is a very long process and when English is not your mother tongue, this is at the end more difficult. You also have to target the proper journal, not too high but not too low either. Raising funds permanently is also challenging. Finally, the time elapsed in making science is really reduced.

Pleuni: I know you live in a different country now than where you did your studies. When and why did you decide to move to South America from France?

Dr Lise Musset: I finally cheated because indeed I did my studies in France and my post-doctorate in the United States but I grew up a large part of my childhood and my adolescence in French Guiana. So finally, 15 years ago, it was more a return home than a great departure for new adventures. The adventures were new professionally but not personally and at the level of the place of life.

Pleuni: Did you always know you would be a scientist studying malaria parasites?

Dr Lise Musset: Of course not. First I made my choices according to my favorite subject in high school. I was, and I am always, fascinated by life sciences and more particularly the exceptional functioning of the human body and health. It was obvious to orient myself towards health studies. Only after getting the Bachelor’s, I chose to add research to my curriculum. The attraction of understanding things, discovering and elucidating biological mechanisms did the rest.

Pleuni: Do you always do science or do you have other interests too?

Dr Lise Musset: I have several other interests and as a woman I always try to find an equilibrium between professional life and personal life. It is not easy and you always feel you do not do enough in one part or another. I have three girls. I have been an administrative manager of a gymnastic club of 140 gymnasts, I have been a dancer since I was 6 years old, and I am in charge of the management of a joint property with apartments. So my days are really full and there is no time to be bored.

Pleuni: As you know, I am really interested in drug resistance. Why do you think drug resistance to some malaria drugs (e.g. Pyrimethamine) is very common, whereas resistance to Atovaquone is not so common?

Dr Lise Musset: The spread of drug resistance is dependent on several parameters, which include the molecular basis for resistance, the drug pressure applied on the parasite population, the fitness cost of resistance and the usage of drugs by people. Pyrimethamine has been largely used in endemic areas and the three mutations responsible for resistance were widely spread throughout all transmission areas. In some places such as in Amazonia, those mutations are fixed in the population meaning there are no more parasites carrying the wild type genotype. For Atovaquone, the context is different because this molecule has not been used at a large scale in endemic areas except to treat imported malaria in Europe and the US. Recent work recently demonstrated that the mutation responsible for resistance (pfcytb Y268S) is not transmitted to mosquitoes which could limit the resistance spread even in endemic area. However, I will not recommend using it in endemic countries to avoid losing its efficiency.

Pleuni: Do you think malaria will ever be eradicated?

Dr Lise Musset: We have efficacious treatment and rapid diagnosis methods. Therefore, elimination of malaria is feasible in some countries where coordination, competencies against malaria and health care systems are strong enough to pursue the fight against malaria for several years. Global malaria eradication is another game. All the countries have to reach local elimination first. Regarding the poverty and instabilities lived in some countries, it appears very complicated to reach eradication.

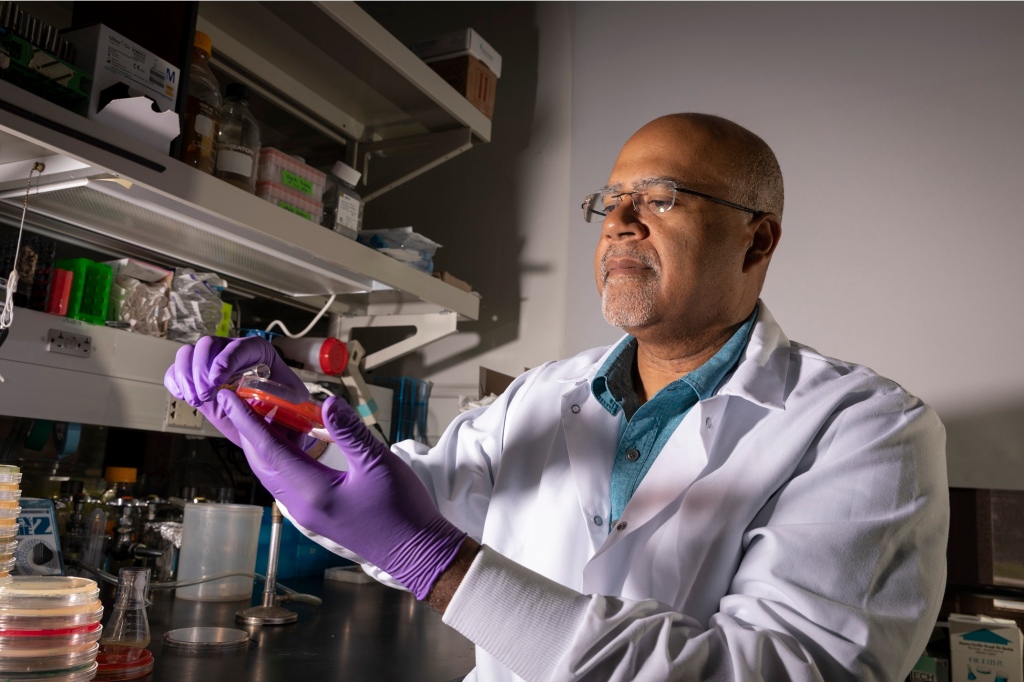

Lise Musset, researcher, shown here working in the lab.

Lise Musset, dancer, shown here while dancing with a partner.

I got to know Nandita Garud when she was a PhD student in the biology department at Stanford and I was a postdoc there. While we were in the same lab, we got to collaborate on two papers: one about population genetics and drug resistance evolution and one about rats in New York City. After finishing her PhD, Nandita worked at UCSF as a postdoc and then took a job as an assistant professor at UCLA. You can read more about her interesting work on the microbiome, fruit flies and other topics on her website. I asked her about a recent paper on using supervised and unsupervised methods to analyze microbiome data.

Pleuni: Hi Nandita! Thanks for taking the time to chat with me! Can you tell me in a few sentences what your job is?

Nandita: Hi Pleuni! Thank you so much for inviting me to chat about my work. I am an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at UCLA. My research is on understanding the evolutionary dynamics of natural populations, currently with a focus on the human microbiome, but I also work on Drosophila and other organisms! My research group (or, ‘lab’) consists of several PhD students that perform computational work to understand how natural populations evolve.

Pleuni: So, you consider the community of microbes that live in my intestinal tract as a natural population, is that right? And they evolve?

Nandita: That’s correct. I consider populations that live outside a test tube in the lab to be natural populations. Interestingly, gut microbiota can evolve on even 1-day timescales, even in the absence of a selective pressure like antibiotics!

Pleuni: I saw that you published a paper about supervised and unsupervised methods for background noise correction in human gut microbiome data. Could you explain what the human gut microbiome is? And why you need background noise correction for it?

Nandita: The human gut microbiome is a complex community that is composed of hundreds of microbial species coexisting and interacting with one another. The human microbiome is known to play an essential role in health, and changes in the microbiome are associated with numerous diseases like diabetes, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease. Being able to predict disease status from the human microbiome is important for helping individuals diagnose any illnesses they may have. One major complication, however, is that technical variables, such as how the DNA was extracted from the sample, can introduce noise in the data, making it harder to predict human phenotypes. So, background noise correction is an important approach for addressing this data heterogeneity so that more reliable predictions can be made.

Pleuni: Thanks! In the new paper from your lab, you compare supervised methods (which are currently standard for noise correction) and unsupervised methods (which have not been applied to microbiome data). What is the difference here between supervised and unsupervised methods?

Nandita: Supervised methods are ones where a machine is shown labeled data and is trained to understand the differences between data classes. Unsupervised methods are ones where the machine needs to figure out on its own what groupings are present in the data. We use an unsupervised approach because we don’t always know what sources of noise contribute to variation in the data.

Pleuni: Okay, thanks! So, I imagine something like this: If microbial species A is always 2x as abundant in samples that were sequenced with machine X vs machine Y, then we can correct by changing the abundance of species A so that it matches between the two machines? Is that what’s happening?

Nandita: Yes, but we aren’t explicitly adjusting the abundances, rather, throwing away variation due to noise.

Pleuni: Does this mean that you do a dimension reduction method first and then throw away dimensions?

Nandita: Exactly — we do PCA (principal component analysis) and then throw away the first PCs (principal components) because they usually are correlated with noise. We do run the risk of throwing away signal too, but that’s the tradeoff in an unsupervised approach. But when we compare this unsupervised approach to the standard supervised approaches, it can work just as well in many scenarios! And the good thing is that this way we can correct for unidentified confounders.

Pleuni: Cool 😎 Thank you for explaining all of this, Nandita!

I have one more question. What is something you like to do when you are not doing science?

Nandita: I enjoy taking walks with my family and enjoying the outdoors in Los Angeles!

Pleuni: Thank you Nandita!

Here is a link to the paper: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009838

The website of the Garud lab: https://garud.eeb.ucla.edu/

Chris Davies: “Today, we are here to recognize and celebrate these students who began, endured, and successfully completed the PINC, GOLD, or gSTAR certificate programs. I want to begin by saying congratulations and well done. Bringing together the fields of computing and data science with biology and chemistry is a pathway towards the future, that is now. The growth of technology to analyze large data sets, create applications, and the ability to code has never been more important in a generation than it is now. To the dreamers and organizers of these programs, I am happy to say your dream has come true amongst these students today.

For those of you that do not know me, my name is Chris Davies, and I am so honored to be here today speaking to you. My involvement in this celebration today arose from a vision that began with Joy Branford and Marlena Jackson at Genentech. A vision for change and opportunity. To change the face of STEM education, and to provide an opportunity to those that were not born into opportunity. My job at Genentech is to discover next generation medicines that change the lives of the patients that we serve. My job in life is to be Chris, a man that tries to make a difference in the lives of all the individuals that he encounters. I saw the gSTAR program as the opportunity that aligned perfectly with that job description. Alongside, my Genentech colleague, Chunwan, and SF State professor, Anagha, we envisioned a course that not only imparts knowledge to the students, but builds a bridge of life experiences that each student can walk across, allowing them to see and believe that they can achieve and aspire to similar or even greater levels. That vision became CSC 601, a seminar series course that outlined the drug discovery and drug development process from basic biology to post market approval, using current Genentech employees as guest speakers, whose jobs span the entire drug development process. Not only did the speakers talk about their job description and the role it plays in drug development, but also, each speaker outlined their life and career journey, emphasizing the successes, failures, and challenges that have led up to where they are at now.

Chunwan and I were the first “guest speakers.” We introduced the entire drug development process from start to finish. I have to say this was fun! Getting back into the classroom (albeit virtual) to engage with college students brought me back to my days in graduate school. We were able to set to tone and foundation for what was to come during the semester. Think about the timing and relevance of this course topic. We were and still are in the midst of the largest global health pandemic anyone has ever seen. The news was littered with information on the discovery and development of vaccines, followed by more information on vaccine and drug authorizations and approvals. What better way to engage with current events than to impart knowledge, but also make room for open discussion? Just like the rest of the speaker panel, we highlighted our life and career journey. A journey that included for me growing up in Kentucky to Sierra Leonean parents, who immigrated to the United States South in the embers of the Jim Crow era in 1973. A journey that included balancing life as a division I soccer player at Western Kentucky University with a chemistry major, mathematics minor, all while being heavily involved in undergraduate research. A journey that took me to Atlanta, GA for two summers for an internship at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which opened the doors for me to pursue my doctoral degree at Purdue University in Indiana. A journey that led me to pack up my car to drive 2225.5 miles across the country to start a new life in Oakland, CA on a $39k postdoc salary at 26 years old.

As I sat through each class during the semester, I could see the level of engagement from the students and the impact each speaker was making as he or she described their journey and job. My favorite class of the semester was the last class, in which we held an in-person discussion session. I was blown away by the overwhelmingly positive responses and feedback from those that took 601. On behalf of all the guest speakers, I want to thank the 601 students for your willingness to allow us to take you along for the ride through our life and career journey.

That was a little bit about me, my involvement, and appreciation for the gSTAR partnership with SF State. For the second part of this speech, I would like to speak directly to you, students, because we are here to celebrate you and your achievement today. When I was asked to be the speaker at this celebration, I was overwhelmed with humility and honor that I would be entrusted with this responsibility. A responsibility to not only represent myself, Genentech, and the ones who were brave enough to ask me to talk and impart my ridiculousness, that some might call wisdom or encouragement. For those that know me, I love to talk, connect with people through stories, laughing, jokes, and through wrestling with life’s most challenging and deep topics. In order to collect my thoughts to ensure they were coherent, I first went to YouTube and searched for commencement speeches. I listened to speeches from Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey, Denzel Washington, and Chadwick Boseman. Even this past weekend, I heard former NBA champion, Dwayne Wade, give Marquette University’s commencement speech. Each speaker used their life’s journey to impart wisdom to the graduates, in hopes to inspire them as they embark on their next steps. These individuals that I listened to need no introduction. These individuals have done extraordinary things in their lives that we continue to celebrate today, but let us not forget they all started out as people just like you and I. They had upbringings and experiences like many people in this room today, but what was it that separated them from the rest? Was it their talent, resilience, passion, desire, determination, hard work, belief, support system, opportunity, etc? The first thing I want to say to you is that you have to embrace your own journey, it isn’t about comparing yourself to other’s successes or failures, but try to take pieces of others experiences to help propel you on your own path.

There are four things that I have learned along my journey through life that I hope will help inspire you along your own life journey. I continue to live by and struggle through what these four things mean for me in each season of my life. This is an ever changing and ongoing process.

In school, I always did well in math and science, and my dad was/is a chemist, therefore, he pushed my siblings and I towards majoring in chemistry in college. Doing chemistry and working in a lab did not fit for my brother and sister, even though they did it to please my father. For me, once I started doing undergraduate research my second semester of college, chemistry became real for me. I enjoyed it! I learned so much working alongside my professor. I enjoyed getting results and analyzing data, all in pursuit of telling a story of what we think is going on. Soon I realized that working in the lab enabled me to travel all over the United States to go to conferences to present my data, talk to people, and continue to learn even more. Being at a conference opened the door for me to get an internship at the CDC, which exposed me to the world of proteins, biochemistry, but most importantly, that getting a PhD was possible for me. Obtaining a PhD open doors for me to come out here to do a postdoc at UC Berkeley, and then, transition to Genentech. The main takeaway is that it started with my openness to trying something new that ending up being fun and exciting. I had no idea that saying yes back then would lead me to me standing here in front of you today. What I do know is that doing stuff that excited me helped me to navigate the challenging and difficult moments along the way.

Following on from my first point about doing things that you are excited about. I grew up playing soccer since age 5. I played on travel teams, high school varsity, I was a division I soccer player, and I even played for a semi-pro soccer team while pursing my PhD. A typical weekday during graduate school consisted of working in the lab from morning until 5pm, and then, I would leave campus to go to the sports club to coach kids for 2-3 hours, before having my team training for another 2 hours. After practice, we would go eat around 10:30-11PM, and then, I would shower and go to bed to do it all over again the next day. Weekends consisted of playing games locally, or traveling as far as 4-6 hours for away games. As crazy as this schedule was, it brought the perfect balance in my life. When I was at school, I was focused on chemistry, when I left school, I was focused on coaching and playing. The main takeaway here is that seeking balance in your life is healthy and beneficial. I learned to be so much more efficient in my work, but also soccer gave me a release from school, and school gave me a release from soccer.

This I believe is one of the most important things that I’ve learned along the way. Finding people that can help guide you along your path. You do not need people to give you step by step instructions, but you need a mix of people, a board of advisors, that you can lean on a times to help you navigate this journey called life. The key things about mentors are: (1) they do not have to look like you, (2) they do not have to be your friend, (3) they should be people who have your best interest in mind, (4) they should be individuals that challenge you to grow, and (5) they should be people who call you out equally as often as they praise and support you. These are people whose goal and desire is to see you reach your full potential, along your own journey. Sometimes these people are in your life for only a season, others across multiple seasons, but I encourage you to seek these people, be open to learning along the way, and continue to stay connected or in touch, even if it is only for a simple check-in or hello.

I have found that growth and progress is uncomfortable. Some of my greatest successes and accomplishments stemmed from saying yes to stepping into, remaining in, and/or enduring uncomfortable situations and circumstances. The best example in my life was my decision to move out here. I was finishing my doctorate degree and I was still playing soccer, coaching, and I had a couple job opportunities, one in particular to work for my friend/mentor’s company. He painted the picture of learning directly from him in the area of pharmaceutical analysis, while continuing to play and coach soccer. He even proposed that I take over managing the soccer club. To put it simply, I thought this was my dream scenario to do science and soccer. Everything was perfect, I knew the area, the people, and I would still learn and grow in my career, however, there was one thing that held me back from saying yes, this would have been comfortable. I had one opportunity, a postdoc at UC Berkeley, that paid me less, in an area that I knew nothing about, without friends and family, but would be an adventure, especially since I was 26 at the time. I chose to move out here to the unknown instead of staying for the known. I would rather come out here and it not work out, than to be too afraid to try. It was uncomfortable adjusting to life in the Bay Area compared to the south and Midwest. It was uncomfortable having to start life all over again making new friends and learning new routines. It was uncomfortable paying $1100 for an apartment the exact same size as one that I only paid $500 for in Indiana. I had no idea at the time how my life would turn out, but that decision changed my life forever. Just think, I would not be standing before you here today. The main takeaway here is do not be afraid to be uncomfortable because you never know what can come out on the other side.

In closing, I would like to encourage you to dream big and do not be afraid. Congratulations on completing these programs and good luck with the next steps in the journey. Thank you for your time and this opportunity to speak.”

Matt Suntay is one of the students in the PINC program and also a research student in my lab in the E. coli / drug resistance / machine learning team. A few days ago he gave a speech at our PINC/GOLD/gSTAR graduation event. I thought it was a great speech and Matt was kind enough to let me share it here both as a video and the text for those of you who prefer reading.

“To those of you who may know me, you all know I’m pretty adventurous. For those of you who may not know me, first off, my name is Matthew Suntay, and I have jumped off planes, cliffs, and bridges – and each time was just as exhilarating as the last. But, let me tell you about my most favorite jump: the leap of faith I took for the PINC program.

I call it a leap of faith because when I first heard about the PINC program, and specifically CSC 306, I thought, “Ain’t no way this could be for me. I may be stupid because I can barely understand the English in o-chem and now I gotta understand the English in Python? Maaaan, English isn’t even my first language… But they said I don’t need any prior computer science knowledge, so why not? It’s Spring ‘21, new year, new me, right?”

And let me tell you, it definitely made me a new me. I went from printing “Hello World!” to finding genes in Salmonella to constructing machine-learning models to study Alzheimer’s Disease and antibiotic resistance in E. coli. These are some pretty big jumps–my favorite, right?–and they weren’t easy to make. However, I was never scared to make any one of those jumps because of the PINC program.

When I think PINC, I don’t only see lines of code across my screen or cameras turned off on Zoom. I see friends, colleagues, mentors, and teachers. I see a community.

I see a community willing to support me in my efforts to develop myself as a scientist. I see a community providing me the platform and opportunities to grow as a researcher. And most importantly, I see a community that shared hardships, tears, laughter, and success with me.

I can confidently say that the PINC program was, and still is, monumental to my journey through science. Thanks to the PINC program, many doors have been opened to me and one of those doors I’m always happy to walk through each time is the one in Hensill Hall, Room 406 – or the CoDE lab. It was here in this lab that I met some of the most amazing people who want to do nothing but help me reach new heights. I’m so grateful and lucky to have them. So thank you, Dr. Pennings, for believing in me and continuing to believe in me. Thank you to everyone in the CoDE lab for supporting me and laughing at my terrible jokes – and real talk, please keep doing so, I don’t know how to handle the embarrassment that comes after a bad joke.

If I haven’t said it enough already, thank you so much to the PINC program. If you were to ask the me from a year ago what his plans were for the future, he would tell you, “Slow down, dude, I don’t even know I’m trying to eat for breakfast tomorrow.” But now if you were to ask me what my plans for the future are, I’d still tell you I don’t know what I’m trying to eat for breakfast tomorrow because I’m too busy writing code to solve my most current research question, whatever it may be.

For many students, including myself, one of the biggest causes of an existential crisis is, “What am I gonna do after I graduate?” To be honest, I’m still thinking that same thought, but without the dread of an existential crisis. One of the coolest parts of the PINC program is the exposure to research and the biotechnology industry, and learning that research == me and not just != the stereotype of a scientist.

Dr. Yoon, thank you for taking the time and effort to push me and my teammates forward, because even though our projects were difficult, we learned a lot about machine-learning and ourselves, like who knew we had it in us this whole time? You definitely did and you helped us see that. Professor Kulkarni, you also helped us realize that we should give ourselves more credit. 601 and 602 showed us we can be competitive and that we’re worth so much more than we make ourselves out to be. Also, I would like to give a quick shoutout to Chris Davies and Chun-Wan Yan for the wonderful seminars because those talks gave me hope and inspiration for the future. Knowing that there’s something out there for me makes going into the future a lot less scary and a lot more exciting because who knows what awesome opportunity is waiting for me?

And one last honorable mention I would like to make is to Professor Milo Johnson. He was my CSC 306 professor, and I don’t know if he is here today, but he was an amazing teacher in more ways than one. He helped me turn my ideas into possibilities and I have him to thank for helping kick start my journey through PINC. When I thought “I couldn’t do it, this isn’t for me,” he said “Don’t worry, you got this.”

So, once again, to wrap things up, thank you to everyone who’s helped me out this far and continues to help me out. Thank you to all my friends, mentors, and teachers that I’ve met along the way. And thank you to the PINC program, the best jump I’ve ever made.

This letter was written by Mila Hermisson, with the help of her parents, Joachim and Sabine Hermisson. Mila is extremely sick and has been in her bed in total darkness for well over a year now. Her letter was initially published in German on this Kudoboard.

ME/CFS is a very serious disease that can be caused by viral infections. Long Covid can also lead to ME/CFS, which means that the number of patients is expected to rise significantly. Time to learn about ME/CFS!

My name is Mila. I am 19 years old and very seriously ill with ME/CFS. I know that people who are not affected themselves can hardly imagine what that means. That is why I would like to tell you about it here.

Since November 2020, more than 10,000 hours, I have been confined to my bed in total darkness as you can see me in the picture. I can barely move my arms and legs, can’t eat by myself, can’t sit for more than a minute, and haven’t been able to speak for half a year. If I want to communicate something (like here), I can only do it on good days, when I can write letters on my bedsheet with my finger.

But worst of all is the uncertainty, the fright and the total loneliness. Even my cat is too exhausting and can no longer be with me. My parents and nurses are only in the room for the most necessary tasks. Everything has to go quickly and as calmly as possible to avoid stimulus overload and further crashes. Outside, life goes on. My twin sister and my friends have graduated from high school, have been abroad, are starting their studies. I am trapped here, hour after hour, day after day, month after month, in solitary confinement, buried alive.

I was 15 years old when I did not recover after a viral flu in the fall of 2018. In the small picture, I’m already sick, even if you can’t see it. In the early years, with great effort, I still managed to finish 10th and 11th grade. Today, I know that it was not good for my health, but I had so many plans. I was used to not losing optimism and going my way despite difficulties. Today, after my severe crash, my only hope is that the disease will finally be recognized, that there will be research and, as soon as possible, a therapy.

ME/CFS is a terrible disease that takes away my youth and can completely destroy a life. There are so many people affected, the stories on this page are just examples. And it can strike anyone. Given this, it’s hard to believe that there is almost no medical care, appalling ignorance and ignorance among many doctors, and far too little research.

Please: Build up care structures at long last! Make postviral diseases a focus of research and medical education and training! Take the experiences of patients seriously and act! Thank you.

Written by Mila Hermisson, Mödling, Austria, 2021.

If reading about Mila and her disease makes you want to take action, here are some suggestions.

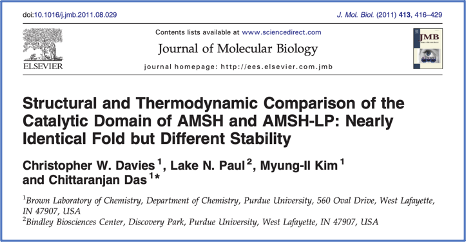

Christopher has a BS in Chemistry from Western Kentucky University where he was also a very successful collegiate soccer player. As an undergrad he did an internship at the CDC. He then went to do a PhD at Purdue University. The title of his thesis was “Structural and Functional Characterization of the Endosome-associated Deubiquitinating Enzyme AMSH.” He published his results in peer-reviewed journals such as the Journal of Molecular Biology (link). He then applied for and got a postdoc fellowship from the National Institutes of Health to go to UC Berkeley to do a postdoc. From there he got a job at Genentech and now has been there for 6 years.

1. How did you decide to get a degree in biochemistry? What interested you in making this choice? What were the challenges (if any) and were your successes that drove you to achieve this degree?

My first experience working with proteins came during my summer internship at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) after my junior year in college. After that summer at the CDC, I returned for my senior year in college, took a biochemistry course and a nutrition course, and I thoroughly enjoyed how practical and applicable biochemistry is to all of us. From here, I knew I would pursue my graduate studies in biochemistry. The main challenge that I had going into graduate school was that I was a chemistry and mathematics major in undergrad, therefore, I had to spend a lot of time learning the basic biology concepts. Overall, my passion for learning the interface between chemistry and biology really drove me to successfully obtaining my doctorate degree in biochemistry.

2. Why are you interested in a career in Biotech? What inspires you about this work?

I am interested in biotech because this is an industry in which you can make a tangible and life-changing impact in the lives of patients. Coming out of my postdoc, I wanted to my work on real drug discovery, and learn about how basic research can be turned into drugs that make a difference. The ability to be involved in and around people who have discovered impactful medicines inspires me every day.

3. What do you want to do in your future career? What are you aiming for?

In my future career, I want to learn about how the other parts of the organization, outside of early research, fit together to form an impactful organization that makes a difference in the lives of patients.

4. In your opinion, why should a student at SF State consider a career in Biotech?

An SF State student should consider a career in biotech because this is an industry in which you can make a broad, impactful difference in the lives of people, while also being at the center of innovation.

5. Can you share something interesting about yourself?

I played soccer my entire life since I was 5 years old. I played division I college soccer, semi-professionally while pursuing my doctorate degree, and I traveled to three European tournaments with the Genentech soccer team.