Dr Lise Musset is a malaria researcher in French Guiana in South America. I learned about her work years ago. In 2005, she published a paper to show that resistance to the drug Atovaquone is very rare in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Then, in 2007, she published another paper that showed that Plasmodium falciparum can evolve to become resistant to Atovaquone inside of people who are taking the drug to treat a malaria infection. There seemed to be an interesting contradiction here. Why is this type of resistance rare, even though we see that it can evolve within patients? Usually when resistant strains of malaria evolve within a patient, they will then spread from patient to patient, which makes the resistance become more common. The combined results of Dr Musset’s papers therefore suggested that the resistance is uncommon because, even though it can evolve, the resistant parasites cannot spread to other patients.

Much later other researchers showed that the resistant parasites cannot survive well in mosquitoes. This is a classic example of a tradeoff: a genetic change makes it so that the parasite can survive in the presence of the drug Atovaquone, but the same genetic change makes it unable to survive in a mosquito. Good for us and interesting science!

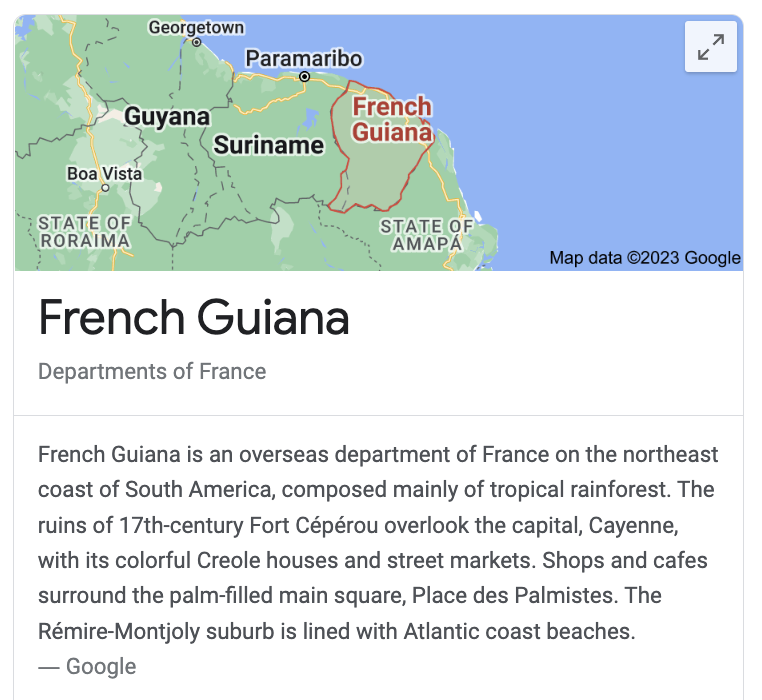

I wanted to ask Dr Musset about her work in French Guiana. In case you are wondering, French Guiana is in South America and it is part of France.

Pleuni: Can you tell me what your job is?

Dr Musset: I am a pharmacist and research director at the Institut Pasteur de la Guyane working on malaria. My work is passionate and very diverse, being a health professional as a medical biologist, researcher and expert in public health.

Pleuni: You studied to be a medical doctor, is that right? – but you work as a researcher. How did that come about?

Dr Lise Musset: I studied to become a pharmacist, which I am, but I rapidly wished to specialize in research. My main motivation during my education process was always to keep the maximum number of doors open. Therefore, in addition to the pharmacist diploma, I began to prepare for a Master in Science and then, to defend a PhD in parasitology. My curiosity and my origins from the tropical area probably played a role in the choice of research in infectious diseases mainly observed in the tropical places of the world.

Pleuni: What is the most fun part of your job?

Dr Lise Musset: My favorite part is when we analyze the results obtained after a long process which generally begins with writing a project, raising funds and all the administrative and ethical parts. Also, I really like to go in the field, in contact with people living in malaria endemic regions and try to implement operational research projects to enhance malaria care. My research is at the frontier between fundamental research and public health because my lab is a reference lab at the national (National Reference Center) and international level (WHO Collaborating Center). Our final aim is always to improve care.

Pleuni: What part of your job do you find difficult?

Dr Lise Musset: The most difficult part is to valorize the data and to publish them. Writing is a very long process and when English is not your mother tongue, this is at the end more difficult. You also have to target the proper journal, not too high but not too low either. Raising funds permanently is also challenging. Finally, the time elapsed in making science is really reduced.

Pleuni: I know you live in a different country now than where you did your studies. When and why did you decide to move to South America from France?

Dr Lise Musset: I finally cheated because indeed I did my studies in France and my post-doctorate in the United States but I grew up a large part of my childhood and my adolescence in French Guiana. So finally, 15 years ago, it was more a return home than a great departure for new adventures. The adventures were new professionally but not personally and at the level of the place of life.

Pleuni: Did you always know you would be a scientist studying malaria parasites?

Dr Lise Musset: Of course not. First I made my choices according to my favorite subject in high school. I was, and I am always, fascinated by life sciences and more particularly the exceptional functioning of the human body and health. It was obvious to orient myself towards health studies. Only after getting the Bachelor’s, I chose to add research to my curriculum. The attraction of understanding things, discovering and elucidating biological mechanisms did the rest.

Pleuni: Do you always do science or do you have other interests too?

Dr Lise Musset: I have several other interests and as a woman I always try to find an equilibrium between professional life and personal life. It is not easy and you always feel you do not do enough in one part or another. I have three girls. I have been an administrative manager of a gymnastic club of 140 gymnasts, I have been a dancer since I was 6 years old, and I am in charge of the management of a joint property with apartments. So my days are really full and there is no time to be bored.

Pleuni: As you know, I am really interested in drug resistance. Why do you think drug resistance to some malaria drugs (e.g. Pyrimethamine) is very common, whereas resistance to Atovaquone is not so common?

Dr Lise Musset: The spread of drug resistance is dependent on several parameters, which include the molecular basis for resistance, the drug pressure applied on the parasite population, the fitness cost of resistance and the usage of drugs by people. Pyrimethamine has been largely used in endemic areas and the three mutations responsible for resistance were widely spread throughout all transmission areas. In some places such as in Amazonia, those mutations are fixed in the population meaning there are no more parasites carrying the wild type genotype. For Atovaquone, the context is different because this molecule has not been used at a large scale in endemic areas except to treat imported malaria in Europe and the US. Recent work recently demonstrated that the mutation responsible for resistance (pfcytb Y268S) is not transmitted to mosquitoes which could limit the resistance spread even in endemic area. However, I will not recommend using it in endemic countries to avoid losing its efficiency.

Pleuni: Do you think malaria will ever be eradicated?

Dr Lise Musset: We have efficacious treatment and rapid diagnosis methods. Therefore, elimination of malaria is feasible in some countries where coordination, competencies against malaria and health care systems are strong enough to pursue the fight against malaria for several years. Global malaria eradication is another game. All the countries have to reach local elimination first. Regarding the poverty and instabilities lived in some countries, it appears very complicated to reach eradication.

Lise Musset, researcher, shown here working in the lab.

Lise Musset, dancer, shown here while dancing with a partner.